Lithium extraction for the batteries in our computers, telephones and electric cars is using many of the scarce water resources that allow indigenous peoples and animals to inhabit the world’s driest desert.

Nikolaj Houmann Mortensen / @DanWatchDK

When you arrive in Chile’s Atacama Desert, it seems immediately obvious why space researchers use the region to simulate Mars. The endless red-brown and white plains of sand, rubble and salt that are surrounded by massive mountain ranges and volcanic craters make it easy to imagine you are on a different planet.

According to the astronomy obsessed Chilean movie director Patricio Guzmán, the Atacama is “the only brown dot without any humidity” when you observe Earth from space. Averaging only 15 millimetres of rain each year, the desert is considered the driest place on the globe. Driving from the Pacific coast into the mainland, a few landmarks in the desolate landscape remind you that you are still on the human planet – ghost towns from bygone mining industries that used to extract once-valuable minerals like saltpetre, now stand abandoned in the sand.

There are more signs of life toward the eastern part of the desert. The rare Andean flamingo nests near the saltwater wetlands, and goats graze at the scattered oases that indigenous communities have inhabited for hundreds or thousands of years.

It is also in this part of the desert that humans, driven by a novel global demand, are starting to leave a new mark on the landscape.

Beneath the Atacama and the adjoining salt flats, Chile is estimated to possess more than half of the global reserve of lithium. The light metal is an essential ingredient for making the batteries in our telephones and computers, as well as the electric vehicles (EVs) that are often seen as essential for a green energy transition. As the EV industry soars, the global demand for lithium is expected to increase to almost 10 times its current market size by 2030, leading to a “white gold rush” in Chile and its neighbouring countries.

But extracting Atacama’s lithium requires massive amounts of the scarce water resources that indigenous peoples and animals have relied on to survive for thousands of years in this harsh environment. And according to researchers, it is already causing lasting damage to the fragile ecosystem in the driest place in the world.

IMPOSSIBLE TO GROW WHAT THEIR PARENTS GREW

Coyo is one of dozens of indigenous Likanantaí communities that have existed in the small oases of the Atacama for centuries. The community members take turns to tap the San Pedro River water and after waiting for two weeks, it is finally Hugo Díaz’ time to water his crops. Just like his ancestors used to, the 58-year-old farmer directs water through small canals in a simple irrigation system that distributes the stream to the local residents. But while Hugo Díaz’ parents and grandparents used to grow enough alfalfa plants and grass to feed cattle in their hundreds throughout the winter, such things are far from possible today, he says.

“Today, very few farmers can make a living. We don’t even have 20 percent of the water we need”, the farmer notes and points to markings in the irrigation canal above the water’s surface that bears witness to the higher water levels in the past.

Many of the Atacama’s indigenous residents recognise that climate change is accelerating the water scarcity in the desert, but they say the change started with the arrival of lithium and copper extraction in the area.

“Before the mining companies arrived here, there was plenty of water”, Hugo Díaz says.

THE SAUDI ARABIA OF LITHIUM

With incomparable reserves of lithium, whose crucial importance to the energy sector continues to grow, Chile has occasionally been labelled ‘The Saudi Arabia of Lithium’. Almost 40 percent of the global supply has come from Chile over the past 20 years and, as Danwatch can reveal, it ends up in some of the most popular electronics and electric cars.

Chilean lithium can be extracted at low cost from lithium-containing brine that miners pump up from a massive reservoir beneath the Atacama salt flat. The brine forms enormous ponds on the desert’s surface and the water quickly evaporates away, thanks to the highest levels of solar radiation in the world. The lithium can then be scooped up along with other salts and minerals.

But during this process, up to 95 percent of the extracted brine evaporates into the air. And this accelerates the water scarcity in the Atacama, says Ingrid Garcés, a professor of engineering at Chile’s University of Antofagasta who researches salt flats.

“In Chile, lithium extraction has been regarded as a regular type of mining, as if you were extracting hard-rock. But this is not regular mining – it is water mining”, she says.

The two companies behind the lithium extraction in the Atacama, Chilean Soc. Quimica & Minera de Chile (SQM) and US American Albemarle Corp., have licences to extract almost 2,000 litres of brine per second. Besides the brine, lithium miners also extract considerable quantities of freshwater, as do nearby copper mines.

“The consequence is an impact on the biodiversity in general. And you can see that impact already – the wetlands are drying out”, says Ingrid Garcés.

ANECDOTAL EVIDENCE HAS NOT BEEN TRUSTED

Grass and rushes surround the Tebinquiche lagoon, which suddenly emerge from the seemingly endless and barren salt crust half an hour’s drive from Coyo. The lagoon is important to nearby communities as villagers used to graze their animals on its adjoining pastures. Jorge Álvarez Sandón, a 46-year-old Coyo resident, points to the large white areas that surround the banks of the dark blue water.

“All those white parts used to be covered with water. But the lagoon is getting smaller. It used to be gigantic”.

Atacama’s indigenous communities have sounded the alarm about water scarcity for years. Rivers, lagoons and meadows have all dwindled over the past decade according to the Atacama People’s Council, which represents 18 indigenous communities.

But Chilean authorities have largely relied on environmental impact studies conducted by the mining companies. And these studies have generally not identified significant effects on water levels or the surrounding nature.

“For local people, the change is so obvious – they notice there is less water for their animals, and they see how the rivers are drying out. But this anecdotal knowledge has not been taken seriously by the companies or the state”, says Cristina Dorador, a biologist and associate professor at Chile’s University of Antofagasta, who studies microbial life in the Atacama.

A “MAJOR STRESSOR TO ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION”

A lack of government data and comprehensive independent research has generally made it difficult for environmentalists, concerned scientists and local communities to challenge reports from the mining companies. But independent studies have recently been published that support their claims.

This year, the most comprehensive independent research on the environmental consequences of lithium mining in the Atacama to date, was published by researchers from Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability in the United States. The study recorded key environmental indicators such as vegetation, soil moisture and surface temperatures along with detailed satellite imagery for the period between 1997 and 2017. Researchers observed significant degradation of the Atacama environment over the past 20 years, including increased drought and a decline in vegetation.

While the researchers point to heightened tourism and a growing population as other significant contributors to the environmental decline, they identify ”lithium mining activities as one of the major stressors to the local environmental degradation” and observe a clear negative correlation between lithium mining and vegetation and soil moisture in the Atacama.

Intentar afegir GIF de fotos satèl·lit que mostren expansió de mineria aquí: https://danwatch.dk/en/undersoegelse/our-demand-for-electric-cars-and-smartphones-is-drying-up-the-most-arid-place-in-the-world/

In August this year, an analysis of satellite images by the satellite analytics firm SpaceKnow and the science magazine Engineering & Technology came to a similar conclusion. Based on satellite photos from 2015 to 2019, they observed a strong inverse relationship between water levels at SQM’s lithium ponds and the surrounding lagoons: “as water levels in SQM’s ponds increased, those in the lagoons would drop”.

COMPANIES CRITICISE STUDIES

Both SQM and Albemarle tell Danwatch that the results of the two studies are contrary to the companies’ ongoing monitoring of the areas. Albemarle criticises the researchers for only using indirect data when looking into the correlation between brine extraction and environmental degradation and not including the field data that Albemarle provides.

“We have an extensive monitoring network, which measures water levels, chemistry, evaporation, vegetation cover, flows from natural channels, and of course satellite images too, and when this data is analysed in an integrated way, it is clear that there is no negative impact from our brine extraction in the lagoon systems”, writes Albemarle’s Country Manager in Chile, Ellen Lenny-Pessagno, in an email to Danwatch.

Responding to the critique, Datu Buyung Agusdinata, Assistant Professor at Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability and one of the authors of the study on environmental degradation, writes that supplementary data would enhance future research on this matter but that the study uses a widely accepted approach.

“As to the methodology that we applied in this study, remote sensing is a well-developed technique that is widely applied in environmental assessment studies for detecting environmental changes in diverse landscapes”, Datu Buyung Agusdinata writes to Danwatch.

FROM THE CENTRE OF A CUP

One of the main areas of conflict centres on how the freshwater and brine deposits interact beneath the salt flat and how that may affect water scarcity in the area. While the brine’s high salinity makes it unsuitable for human consumption, it is still in “hydrodynamic relation with the surroundings” according to the Arizona State paper, meaning that intensive extraction can eat into the Atacama’s little freshwater resources causing “negative effects on aquifer depletion, hydric balance and ecosystems”.

SQM and Albemarle however claim that brine extraction does not impact the area’s freshwater recharge. Among their arguments is that the brine and freshwater deposits are separated by a hard crust of salt, and because the different densities of the brine and water prevent them from mixing.

But Ingrid Garcés argues that the salt crust will not keep the freshwater and brine from mixing. She compares the brine extraction to drawing water from one side of a cup

“If someone extracts water from the centre of the salt flat the water is still going to be affected in the surroundings”, she says.

RESIDENTS STILL HAVE NO RUNNING WATER

Last year, the Chilean government’s Committee of Non-Metallic Mining released a report saying that from 2000 to 2015, the amount of water that was extracted from the Atacama was 21 percent higher than the flow of water to the area. The committee linked increased brine extraction with falling groundwater levels and stated that water levels in some wells on the southern part of the Atacama salt flat had dropped by around one meter over the past ten years. Water levels in wells close to the extraction sites had fallen even more.

While Peine, the community closest to the extraction site, experience water cuts for days during the summer, Albemarle and SQM together are licenced to extract a little under 2,000 litres of brine per second.

“This overexploitation is one of the main worries of the communities because many residents here still don’t have proper access to fresh water, while these companies pump up so much brine”, says Sergio Cubillos, resident of Peine and president of the Atacama People’s Council that represents 18 surrounding communities.

“I think mining can be done, but moderately”, says Orlando Martinez, a farmer from the Coyo community.

“Not like SQM is doing now – they just take out water with no control from the government”.

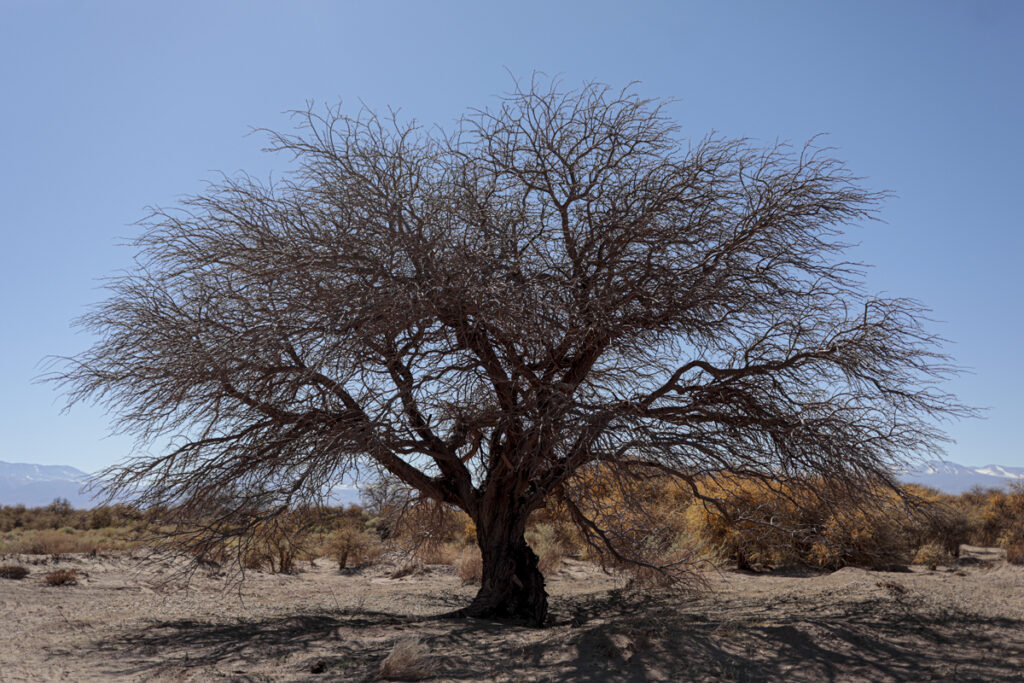

THE TREES THAT SOUND THE ALARM

A bit south of Coyo Thomas Vilca’s shoes break through the dry soil crust as he steps closer to the roots of a massive, native Algarrobo tree. His foot passes through a cavity that has formed beneath the crust in the absence of any humidity in the sandy soil. The 55-year-old schoolteacher from the indigenous Tulor community points to the trunk of the leafless tree.

“You see those black spots where there is a type of fluid coming out? They do that when they are dying. Like they are trying to water themselves”, he says.

The Algarrobo holds a unique cultural and spiritual value to the local Likanantaí communities of the Atacama. It is one of many trees and plants that they say is increasingly succumbing to the dry climate. Furthermore, their ill health can be an early warning sign for a severe water scarcity – the Algarrobo is a drought-tolerant species known to grow roots deep into underground water reservoirs.

It was also Algarrobo trees that were the centre of a government inspection report from 2013. Inspectors found that SQM had failed to inform authorities that one third of the trees on SQM’s property, which the company had committed to monitor, were dying. Even more trees were dying two years later, according to government inspection reports reviewed by Reuters, and SQM were still largely ignoring these warning signs.

A TASTE OF WHAT IS AHEAD OF US

Ironically, the Atacama salt flat was once a major lake before it dried up as a result of severe climate changes thousands of years ago. Scientists now study the desert as an example of what could happen to ecosystems elsewhere around the planet as global climate change takes hold. But in the push to mitigate rising temperatures by replacing conventional vehicles with electric, industries are sucking out the little water that’s left in the world’s driest desert.

“With the Atacama’s very little rains, we expected that in about one hundred thousand years this place would be completely dry. But now human activities are accelerating the process on a scale that we had never thought possible before”, says Cristina Dorador, the biologist.

FLAMINGOS AND MICRO DISASTERS

Jorge Álvarez Sandón remembers when the Tebinquiche lagoon was filled with flamingos. The desert used to be home to the greatest population of the Andean flamingos in the high Andes as the species come here to nest. There would be enough eggs for the Likanantaí to gather some and trade them with other indigenous communities.

“But now the water level is very low and that doesn’t work for the flamingos”, says Matilde López, a biologist and researcher at the Faculty of Forest Sciences and Nature Conservation of the University of Chile.

She has studied the fauna of the Atacama for decades and she now fears that lithium mining could be the end of the flamingo populations here. If the water in the lagoons shrinks, the salinity increases and the algae populations decreases, which is what the flamingos live on.

“So, you break the whole food chain”, she says.

Similarly, Cristina Dorador fears that the Atacama may undergo what she terms a “micro-disaster” in which changes to the unique microbial life of the desert may have immense consequences for the desert’s flora and fauna.

“If there are some changes either in the water levels or the salinity of the water, it can affect microbial communities and at the same time affect the whole structure of the ecosystem”, she says.

A LACK OF CONTROL

In 2017, then-head of Chile’s state development agency, CORFO, sent a letter to Chile’s environmental regulator, in which he warned that SQM was posing “a serious risk to the stability” of the ecosystem of the Atacama and its brine reserves.

Reuters has previously revealed how both Albemarle and SQM have voiced concerns over the other’s overexploitation of the brine reserves in filings with Chile’s environmental regulator, while simultaneously expressing that they were very confident about the quantities and future supply of the reserves in public statements.

The former government founded the Committee of Non-Metallic Mining – the institution that measured that the amount of water being extracted was much higher than what was flowing into the Atacama – which was working on a strategy that would allow the Chilean authorities to independently monitor the environmental impact of mining in the Atacama. But when a new centre-right government took office last year, it shut down the committee.

“The few studies I can refer to, I got from the work done by the researchers in the Committee of Non-Metallic Mining”, says Marcela Hernando, an MP from the centrist Radical Party and former mayor and regional governor of the Antofagasta region in the Atacama.

STATE AGENCY HAS NEVER HEARD OF ENVIRONMENTAL STUDY

Marcela Hernando agrees with concerned scientists and environmental organizations who point out that the government water authority, Dirección General de Aguas (DGA), which should play an essential oversight role, is massively underfunded. “The DGA has very few people, and in the vastness of the desert and its thousands of kilometres, it is very difficult to make inspections”, she says.

When Danwatch meets the government water authority at the Ministry of Public Works in central Santiago, Head of the Department of Conservation and Protection of Water Resources, Mónica Musalem, does not think that the current extraction levels pose any major risks for the environment, flora or fauna of the Atacama. She admits that some inspections showed that SQM exceeded the maximum extraction limit back in 2016 and 2017, but she stresses that the environmental authority has since sanctioned the company and set demands on the company which is yet to be evaluated again.

Mónica Musalem also recognises that there is currently more water being extracted from the Atacama than what is flowing to the area.

“But as we are talking about brine water with a high concentration of salt and is not suitable for humans or for anyone, we permitted this hydric disbalance. What we are trying to evaluate is how much we can exceed this water system balance without affecting the environment,” she says.

“This is based on an analysis by the environmental evaluation process which has confirmed that this disbalance will not have negative effects on the environment.”

When Danwatch asks Mónica Musalem about the eight-month-old Arizona State University study about environmental degradation of the Atacama, which most interviewed scientists has referred to, she says she has not heard of it. However, she promptly rejects the satellite image analysis by SpaceKnow and Engineering & Technology saying that water levels in the lagoons show variations from year to year, which is why the structures of the lagoons cannot be seen as a direct indication of the water extracted in the lithium mining process.

ACKNOWLEDGES POTENTIAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

It is the Chilean State Development Agency CORFO which owns the mining concessions at the Atacama salt flat and leases them to the lithium-mining companies. Like the DGA, CORFO vice-president Antonia Eyzaguirre Altamirano acknowledges that there is currently more water being extracted than what is flowing to the Atacama. And such a hydric disbalance caused by human extraction can “eventually have an effect on groundwater levels in some sectors of the basin and a potential impact on surface plant cover”, Antonia Eyzaguirre Altamirano writes in an email.

Considering this, CORFO says it is currently developing a research model that should be able to simulate various scenarios under current extraction quotas. When completed, it will be shared with the relevant environmental authorities as well as the DGA. Furthermore, the agency is implementing an online monitoring system of water and biotic variables to detect water level drops around surrounding wells, Antonia Eyzaguirre Altamirano says. For now, CORFO does not think that current extraction rights should be limited.

OVER EXTRACTION IS THE RESULT OF NEW INTERPRETATION OF RULES

Ellen Lenny-Pessagno, Albemarle Chile Country Manager, emphasises that the company can detect impacts on the environment using new technology and an early warning plan, and reduce brine pumping if the monitored levels drop below a certain threshold. She also notes that Albemarle uses little of its freshwater rights compared to SQM and other companies operating nearby, such as those in the copper mining industry, and that Albemarle is only authorised to pump up 442 litres per second of brine, while SQM pumps up 1,500 litres per second.

“The Atacama salt flat requires joint action by all the involved companies. In this basin there is not only SQM, there are also copper mining operations that extract water and are awaiting evaluation of projects that will extend their extractions, which may affect the recharge of the salt flat”, Ellen Lenny-Pessagno writes in an email to Danwatch.

Alejandro Bucher, SQM senior vice president for technology, communities and the environment, admits that the company over extracted brine in 2016, but he claims that this was due to new interpretations of the extraction regulations by the environmental authority. The company has since filed several suggested plans for a reduced extraction with environmental regulators who finally approved a plan this year, which the company must now execute.

“This authorisation is obtained as a result of an extensive environmental assessment approved by the authority, which seeks to ensure the extraction of brine from the project is carried out without causing an impact on sensitive areas of environmental interest and nearby communities”, Alejandro Bucher writes.